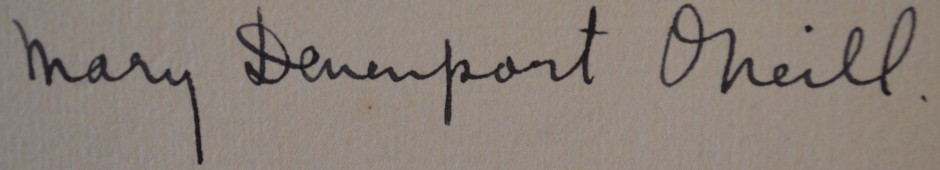

Mary Devenport O’Neill was the first Irish author to publish a volume of modernist poetry besides W.B. Yeats. It was entitled Prometheus and Other Poems and published by Jonathan Cape in 1929. Although this was her only poetry collection, The Dublin Magazine faithfully published her poems and verse-plays throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Motifs of temporal flux and gendered power struggles are juxtaposed within her work with themes from classical myth and Irish folklore. The Irish Celtic revival was often in tension with the general narrative of international modernism, and Devenport frequently reacted against the former while taking themes from the latter; however, her poetry also interacts with and often resists many of the dominant narratives in both. Deliberately and determinedly imagistic and terse, her lyrics are pruned with intellectual rigour. She is aware of her own internal censors who suppress specifically revealing narratives and she often uses textual disguise to express overt passion and emotion. She recognised the constraints of women’s creativity initiating a distinct female perspective in response to the androcentric omniscient poetic viewpoint prevalent in romanticism and in the Celtic revival.

An array of characters and poetic speakers inhabit her verse, from argumentative Greek mythological gods, tyrannical dukes and kings, to wise old Waterford women, drugged wives and femme fatales. An imperious Dante, a cat loving Proust, and a hurricane of Richard Strauss’s music, all reflect her individual imagination as well as the cultural influences of her time. Her inspiration comes from nature, yellow leaves of aspen trees and great unattending ocean waves often acting as discursive vehicles to express her own distinctive modernist female aesthetic. This imagined natural world is often influenced by tropes from ancient Irish poetic sources. Beneath Devenport’s four ‘Dream Poems’ lies the indeterminacy of the unconscious that they paradoxically hide and reveal. Thematically, the dream poems respond to hierarchical systems within Irish society, disclosing interrogation of social structures which imposed regulations on women. Throughout her work, her extraordinary prescience as a feminist and proto-ecofeminist anticipates themes by Ireland’s later women poets.

Because Devenport’s poetry is no longer available in print it has been impossible to form a cohesive sense of her body of work. Although her poetry is aesthetically valuable and she was championed by her peers, she was subsequently forgotten by literary history. Accounts of her era briefly mention her as a cultural hostess and wife of Education Minister and author Joseph O’Neill. This project compiles Devenport’s known writing with the exception of her last unpublished play War, The Monster, which was performed by the Abbey Experimental Theatre Company on the Peacock stage in October 1949. Although no longer in print, her poetry has been anthologised: The Oxford Book of Irish Verse, 1912-1958 (1958) includes one of Devenport’s poems, A.A. Kelly’s 1997, Pillars of the House includes some work, in 2008 Earth Voices Whispering: An Anthology of Irish War Poetry 1914 – 1945 edited by Gerald Dawe reproduces Devenport’s only war poem and, more recently, in 2011, Poetry by Women in Ireland edited by Lucy Collins publishes thirteen of Devenport’s poems, the largest anthologised selection of her poetry to date. Both Kelly and Collins recognize Devenport as a modernist writer. Kelly sees her as attempting to break the stereotype of “refined sentimentality” that was often “considered a peculiarly suitable feminine field” (21). Collins writes that Devenport ‘s poetry is “apt for the treatment of tensions between hope and despair, and between purpose and paralysis” (42). Anne Fogarty and Susan Schreibman both discuss Devenport’s poetry in their analysis of forgotten Irish modernist women poets, Fogarty proposing that Devenport writes in “a densely symbolist but vividly concrete mode” as well as having “an anti-sentimental, impersonal, objective style”(89). For, Schreibman Devenport’s poetic “references are at once mythic and local”(315) Gregory A Schirmer cites Devenport’s poetry as showing signs of a “particular interest in imagism” and significantly, he presents her as one of the female poets who “pointed the way toward the relative independence of position and voice achieved by Ireland’s contemporary women poets” (320). This is a reminder that Devenport’s work is important for what it represents about Irish women’s writing as well as for its aesthetic value.

Works Cited

Collins, Lucy, ed. Poetry by Women in Ireland: A Critical Anthology 1870-1970. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 2012. Print.

Fogarty, Anne. “Outside the Mainstream: Irish Women Poets of the 1930s.” Angel Exhaust 17 (1999): 87–92. Print.

Kelly, A. A, ed. Pillars of the House: An Anthology of Verse by Irish Women from 1690 to the Present. Dublin: Wolfhound, 1997. Print.

Schirmer, Gregory A. Out of What Began: A History of Irish Poetry in English. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1998. Print.

Schreibman, Susan. “Irish Women Poets 1929-1959: Some Foremothers.” Colby Quarterly 37.4 (2001): 309–326. Print.