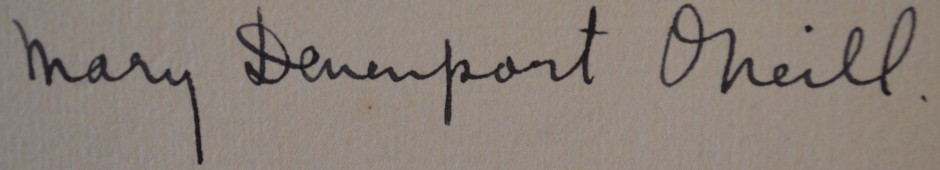

Early Twentieth-Century author at her desk

In 1898, when Mary Devenport was nineteen and took her place in the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, her father was marked as deceased in the college records. He had been a Royal Irish Constabulary sub-constable in Loughrea, County Galway, where Mary was born in 1879. The school record gives her address as the Dominican Convent, Eccles Street, Dublin with a secondary address of Sea Road, Galway. The DMSA waived Devenport’s fee because her family did not earn in excess of 200 pounds a year.[1] She trained there as an art teacher for four years and also completed a summer course in 1907, the year before she married.[2] During her time at the school, her widowed mother Delia and sister Annie moved from Galway to Ranelagh, Dublin[3]. Although there is only scant information on her early life, the Galway landscape and its people retained an imaginative presence in her poetry which often cites locations around the county.

The formative years of Devenport’s life were spent living in Eccles Street. The convent holds incomplete records from these years but many young women were given accommodation while they completed third-level education.[4] While research has not uncovered any written record of her reflections during this time, the influence and philosophy of the Dominican Order played a prominent role in the lives of their students. The convent opened in 1882 as an orphanage for middle-class girls who had fallen on hard times and although this remit had changed by the time Devenport lived at the convent in the 1890s, the ethos of educating girls whose “. . . families were neither poor enough to accept only a national school education for the girls in the family, nor rich enough to afford further education in a boarding school or fee-paying day school” continued to be the school’s focus (Kealy 41). By entering third-level education in Ireland in 1898, Devenport became one of a first wave of women to achieve this educational standard through an entirely Roman Catholic educational system. Only fourteen years earlier four women “made educational history in Ireland” by being the first to matriculate from St Mary’s University College, the university department of Eccles Street (Kealy 132).

Dublin was a small and politically volatile city where a literary career could either be founded or frustrated because of alliances and affiliations. The DMSA provided a fertile breeding ground for the Irish cultural revival of the early-twentieth century and it was here that connections were made between many of the pivotal figures of Devenport’s social milieu. By the time she attended the school a previous generation of eminent Irish literary and artistic figures, including George Russell (Æ) and W.B. Yeats, had been through its doors. John Turpin’s history of the school mentions stained glass artist Harry Clarke’s teaching as an example of how personal connections facilitated publication of work, explaining that “. . . Clarke had contacts with George Russell, editor of the Irish Statesman, and Seamus O’Sullivan, editor of The Dublin Magazine, and managed to get black-and-white work by his students reproduced in these periodicals” (215). Devenport’s social connections were numerous; for example, she attended the DMSA with sixteen-year-old Estella Solomons, who later went on to become a renowned Impressionist artist and social activist. Their names appear on the same page of the entry register[5]. In 1926, after a long courtship, Solomons married Seamus O’Sullivan, editor of The Dublin Magazine, and the couple had a “deep and lasting friendship” with Æ (Coulter 103). This connection is just one of many which characterise the context of Devenport’s literary and artistic life in Dublin.

If Horace’s assertion ut pictura poiesis (as is painting so is poetry) has any credence, the development of a painter’s eye for detail may have formed an aesthetic sensibility significant for Devenport’s later writing. When she attended the school, design classes for women were focused on lace-making and embroidery. Her eye for colour and her close observation of nature may be a consequence of this training in attention to fine detail. Women were taught in separate classrooms from their male peers, and their education had a practical focus. While she was attending college, Devenport “began a correspondence with Joseph O’Neill whose poetry in the Freeman’s Journal she had admired,” and they married in 1908 when she was twenty-nine (Hogan 987). He was a Galway-born Irish scholar who had studied in Manchester and Freiburg before leaving his studies to join the Department of Education as an inspector of primary schools: “He was appointed Permanent Secretary of the Department of Secondary Education in 1923 and remained in this position until his retirement in 1944” (987). Also a poet and author of five novels, he often wrote under various pseudonyms including “Oísin”, “Michael Malia” or the Irish version of his name “Séosamh Ó Néill.” His first verse-play, The Kingdom-Maker (1917), was written in collaboration with Devenport who contributed the lyrics as well as a pencil-sketch of her husband. His position as a senior civil servant placed the couple at the centre of elite political and literary life in Ireland from the 1920s to the ‘40s. O’Neill’s wide ranging interests included Carl Jung’s psychoanalytical theories, Rabindranath Tagore’s writings and “the necessity of every man to find his Karma” (Kelly Lynch 12).

During the 1920s Devenport and her husband bought a home at No. 2 Kenilworth Square, Rathgar, Dublin, where they started a Thursday evening literary salon. Dublin had a circle of established salons, which they called at-homes, and a series of small publications whose editors were part of this social circle. The O’Neills’ salon was attended over a period of years by all of the major literary figures of the time including Æ, Jack B. and W.B. Yeats, Sibyl le Brocquy, Lennox Robinson and Austin Clarke. A feature of international modernism, the literary salon originated in late sixteenth-century France when, according to Olwen Hufton, women of “intellectual distinction” created salons as centres for “refinement and culture” to engage in the “new and developing art of conversation” (433, 434). Presided over by a hostess, the participants exchanged creative ideas and the gathering facilitated intellectual conversation and debate which challenged “the notion of woman as a defective intellect” (434). Tim Armstrong explains that literary modernism’s sites include “salons and galleries” as well as “publications and presses” (24). In 1920s and ‘30s Dublin, this social interaction was critical for the exchange of new ideas in the newly formed Irish Free State. A regular visitor to her salon, W.B. Yeats developed a significant friendship with Devenport, who was fourteen years his junior, while he was writing A Vision. Yeats’s biographers, Hone and Jeffers, mention his connection with the O’Neills, Hone stressing that in the 1920s Yeats “had formed an intellectual bond with Joseph O’Neill . . . and with Mrs. Joseph O’Neill, both of whom had been at more pains than most to discover what he was driving at in A Vision” (373). Yeats’s notebooks from 1921 testify that he discussed his ideas for A Vision with Devenport, making note that “Mrs Joseph O’Neill has set the following question in A Vision”. This is followed by a series of numbered paragraphs where he works out his system of cycles for this work (Yeats).

Writers’ memoirs of the time give a vivid account of salons and many mention Devenport as part of the literary scene. Austin Clarke, poet and founder of the Lyric Theatre Company, gives a lucid description of Æs’ at-homes around the year 1917, mentioning Devenport and her husband. His memoir bears vivid testament to the virtual invisibility of women of this era as artists although they made substantial contributions to contemporary literature. Clarke writes that “every writer or critic who came to Dublin was sure to find his or her way to this Sunday night gathering. . . Everyone talked, smoked, argued – mostly about politics- until ten o’clock” (52, 53). The account of artistic personalities who attended these salons underlines what Armstrong describes as a cultural exchange and flow of ideas between continents:

Among the regular guests were James Stephens, Ernest Boyd and his French wife, Madeleine, Constantine Curran who had written about Italian decorators in eighteenth-century Dublin, Professor Osborn Bergin, caustic Gaelic grammarian and poet, Joseph O’Neill, the novelist, and his wife Mary Davenport [sic], George Moore’s friend, John Eglinton the portrait-painter, Sarah Purser, a witty and redoubtable spinster. F.R. Higgins told me that he had once met Francis Ledwidge there. . . . Once, as we were leaving, I met, on the steps, a small, chubby-faced man with a flowing black tie as large as my own. He was James Cousins, the theosophical poet, back on a visit from India. (Clarke 52, 53)

Clarke corresponded regularly with Devenport during the years 1929 to 1948, and his Lyric Theatre Company produced two of her plays.[6] Devenport’s letters record her involvement with Clarke’s production of her work with a focus on combining choreography with verse. Although Clarke’s memoirs carefully foreground the literary status of each individual present at Æ’s salon, and although he conducted a close artistic collaboration with Devenport over a period of twenty-one years, he nevertheless misspelled her name and described her as the wife of a novelist. Even in 1968 when these memoirs were compiled, it was acceptable for him to ignore her creative output even though elevating her literary status would have enriched his account. The marginality of Devenport’s recorded presence is a reflection of the contradictory role women played within this community of literary patriarchy which supported them although, according to Armstrong, “the canonical narrative of modernism” also neglected women writers (41).

While other memoirs of this period fail to mention Devenport in any context, they reveal bickering and rivalry within this social circle of the creative elite. The novelist Frank O’Connor remembers Irish scholar Osborn Bergin falling out with Joseph O’Neill at one of these gatherings. O’Connor’s memoir incidentally conveys how the support network which the salons provided could equally exclude or intimidate, and how the inclusion or exclusion of individuals within a peer group was an important aspect of these social settings. It also gives a vivid snapshot of a type of machismo and male camaraderie which often insidiously excludes women. Writing of Bergin’s sensitivity towards an imagined slight by Yeats, O’Connor goes on to mention the O’Neills:

But his greatest rancour was reserved for his old friend Joseph O’Neill, a good Celtic scholar, who had been a fellow student of his in Germany. O’Neill – one at least of whose donnish romances will be remembered – married a literary woman, who – again according to Bergin – was always talking of “Péguy and Proust” and getting the pronunciation wrong – a major offence in anyone but an intimate friend . . . . (O’Connor 261)

Although O’Connor links Devenport to literature, he fails to identify her as a poet. Instead, he implies that she was making an intellectual stretch beyond her reach by talking of authors whose names she was not sophisticated to pronounce properly, however, he distances himself from this opinion by reporting it as gossip rather than his own witness.

Apart from writing the lyrics for her husband’s play ten years after she married when she was thirty-eight, Devenport did not publish until 1929 when she was fifty. Her volume of poetry, Prometheus and Other Poems, comprising thirty-three lyric poems, four “dream poems”, one long poem, and a verse-play, was published by Jonathan Cape. However, in 1920 when Æ mentions her in a letter to O’Neill she was forty-one and actively writing. He signed off: “Kind regards to Mrs O’Neill who I imagine is typing up a storm of . . . ideas for her collection” (Russell). In 1933, her verse-play Bluebeard was performed as a ballet-poem in the Abbey Theatre choreographed by Ninette de Valois, who also worked on three of Yeats’s plays for the Abbey. Fifteen years later, in 1948, it was produced by the Lyric Theatre Company. In the same year it was broadcast on The Dublin Magazine Programme on Radio Éireann. Devenport’s 1944 letters mention an earlier production of her Bluebeard by Lara Payne which may have been an amateur performance (“To Clarke” np). Devenport’s verse-play Cain was published in The Dublin Magazine in 1938 and translated into Czech as Kain in 1939. [7] In 1944 Cain was broadcast on Radio Éireann and the following year it was produced by the Lyric Verse Speaking Company on the Peacock stage. In 1947 Out of the Darkness was published in The Dublin Magazine and, two years later, on 17th October 1949, Devenport’s final play, War, The Monster was performed by the Abbey Experimental Theatre Company on the Peacock Stage, but it was unpublished and the play-script is not currently extant.[8] Devenport regularly published her poetry and verse-plays, mostly in The Dublin Magazine, over a period of twenty years, until she left Dublin with her husband when she was seventy.

The O’Neills moved to Nice in 1949 selling their house in Kenilworth Square and all of their possessions. O’Neill revealed his reasons for the move in a letter to R.I. Best: “I’d give my eyes to be back in Dublin but the doctors all warned me that another winter in Dublin would be the death of me and when you’re dead you’ve lost everything.” However, the move was a disaster and O’Neill wrote a poignant letter shortly after their arrival:

I’ve smashed a knee cap and at my age a knee cap does

not cure. I’ll never walk or write again. At times I wish I was dead,

but, if I go, my pension goes with me and my wife will be on the

rocks, for we never saved a penny and I’m not insured. Today for the

first time I realised that I’ll never walk again, a most horrible thought. (O’Neill)

Although none of Devenport’s letters from this period have yet been uncovered, a letter from her husband to a friend conveys her continuing literary ambitions at that time, when he writes: “My wife says she intends going on with her work of writing till she’s a hundred. If she does notch the hundred and I die en route she’ll be in a bad way, for I never insured” (O’Neill). None of Devenport’s work was published after the move to France; she spent her last days living with relatives in Dublin and died in 1967, aged 88 (Hogan 988).

Notes

[1] National Irish Visual Arts Library

[2] National Irish Visual Arts Library

[3] National Archives: 1911 Census

[4] Information from Dominican Convent Archivist, Sr. Catherine Gibson.

[5] N. I. V. A. L. Records

[6] This correspondence comprises 21 letters from Devenport to Clarke often arranging meetings with him N.L.I. Ms 38,665/7

[7] Nli lr 800P60

[8] Cast details www.irishplayography.com

Works Cited

Armstrong, Tim. Modernism: A Cultural History. Cambridge: Polity, 2005. Print.

Brown, Terence. Ireland: A Social and Cultural History 1922-1985. London: Fontana, 1985. Print.

Clarke, Austin. A Penny in the Clouds: More Memories of Ireland and England. London: Routledge & Kegan, 1968. Print.

Coulter, Riann. “A Meeting of Minds: Russell, Solomons and O’Sullivan.” Irish Arts Review 23.1 (2006): 100–105. Print.

Ferriter, Diarmaid. The Transformation of Ireland, 1900-2000. London: Profile, 2004. Print.

Hogan, Robert. Dictionary of Irish Literature. London: Greenwood Press,1996. Print.

Hone, Joseph M. W.B. Yeats, 1865-1939. London: Macmillan & Co, 1942. Print.

Hufton, Olwen. The Prospect Before Her: A History of Women in Western Europe 1500-1800. New York: Vintage, 1998. Print.

Kealy, Máire M. Dominican Education in Ireland, 1820-1930. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2007. Print.

Kelly Lynch, M. “The Smiling Public Man: Joseph O’Neill and His Works.” Journal of Irish Literature 12 (1983): 3–72. Print.

O’Connor, Frank. An Only Child and My Father’s Son: An Autobiography. London: Penguin, 2005. Print.

O’Neill, Joseph. “Letters to R.I.Best.” N.d. MS11003(1). N.L.I.

Turpin, John. A School of Art in Dublin Since the Eighteenth Century: A History of the National College of Art and Design. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1995. Print.