A Leaf in the Wind. By Patrick MacDonogh. (Belfast: Quota Press. net.).

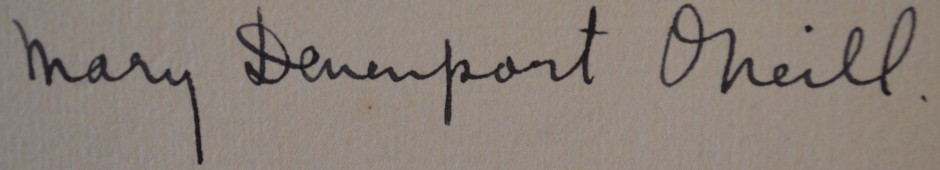

Prometheus and Other Poems. By Mary Davenport O’Neill. (Cape. 5s. net.).

Leaves of Wild Grape. By Helen Hoyt. (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co. net.)

The Best Poems of 1929. Selected by Thomas Moult. (Cape. 6s. net.).

Mr. MacDonogh’s verse is as yet somewhat derivative. Both thought and technique need more concentration and discipline; there are too many weak lines in these poems, which none the less have the appealing fervour and sincerity of adolescence. “To the True Poets” is a sympathetic apologia, and that of most poetic amateurs:

“Condemn us not, immortal few,

Though never we may weave with you

Amid the crown of thornéd rhyme

One blossom from the breast of time

. . . The unresting urge

Still drives us on, still falls the scourge

As cruelly; but warring still

The slow brain and the passionate will

Defeat the soul’s rebellion.”

Prometheus and other Poems provides a contrast in its mature and restless intellectualism. Mrs. O’Neill’s spiritual nostalgia has much in common with the French symbolists in its fin de siécle weariness; indeed the play “Bluebeard” is rather Maeterlinckian. This poet sees perpetually, like her own Storyteller, “across the things that are, the things that may be,” and while observing the changing colours of Nature’s moods, her mind is for ever a-tiptoe with expectation for some more revealing illumination. She excels in the short impressionist poem, and lyrics like “The River Field” and “The Shortest Day” skilfully crystallise a thought or mood in a restricted compass with an accomplished grace. I quote the latter:

“This is the shortest day,

’Tis afternoon;

Warm with the fire I’ve loitered out to see

A pale wet mist

Hiding a yellow moon,

A bunch of jingling stares

Thickening the top of a bare Winter tree.”

It would be hard to imagine anything more boring than the dreams of most people, even those of one’s friends, put into verse, yet included here are four poems about real dreams which I, for one, would have been sorry to miss. The Dante and Virgil one has the bright clarity of a vision, and that about Marcel Proust and the wounded cat, done up by him in a “scrupulous intricacy of splints,” leaves a curiously authentic impression.

Leaves of Wild Grape is a record in intimate, oh! so intimate verse of a woman’s sexual experience: love, marriage, and childbirth. It is all so embarrassingly personal that the reader gets the uncomfortable feeling of inadvertently seeing a stranger’s love letters. It would need the peculiar genius oí a D. H. Lawrence to turn such unreticence into art. There is no transmutation of the personal into the universal, and though the writer evinces a certain feminine sense of beauty in such natural phenomena as trees, flowers, babies, etc., it is all too sentimental and fanciful by half.

Mr. Thomas Moult, who has excellent poetic taste, does admirable service to poetry, in painstakingly collecting each year, the most promising verses from contemporary English, Irish and American magazines. Ireland holds her own here with poems by Æ, R. N. D. Wilson, Katherine Tynan and Irene Haugh, who has a gift for the interpretation of music in verse, though this I fear is less to her credit as a musician than as a poet. To me, however, the two most interesting poems in the book, both by Americans, were “The Virginians are coming again,” a spirited thing, full of vitality, with a superb rhythm, by Vachel Lindsay, and Elinor Wylie’s “Portrait,” of which the subtle wit and peculiarly rare type of perception make one sadly aware how capriciously charming, how debonair and fantastic a writer the world lost by her tragic death last year. “The fair labour of thy verses, Erinna, cries that thou art not perished, but keepest mingled choir with the maidens of Pieria.”

M. S. P.